Mark Twain was a terrible investor. His business ventures went bankrupt, and he had to do his famous speaking tour of Europe to pay off creditors. But he might have been on to something when he said, “Buy land. They’re not making it anymore.” In today’s investment environment, where Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has vastly accelerated the unravelling of 14 years of incompetent Federal Reserve policy, real estate looks like one of the few safe hedges against out-of-control money printing and other problems. But investors have to be very – very – careful.

Three Tipping Points Converge

The sanctions on Russia due to its invasion of Ukraine are likely to tip the United States into a recession. Economists surveyed by the Financial Times expected the first wave of sanctions to cut the average GDP of the NATO alliance members by 0.17%, which would be manageable under normal circumstances. (The World Bank expects Russia’s annual GDP growth to fall by a ruinous 11%.) But these are not normal circumstances.

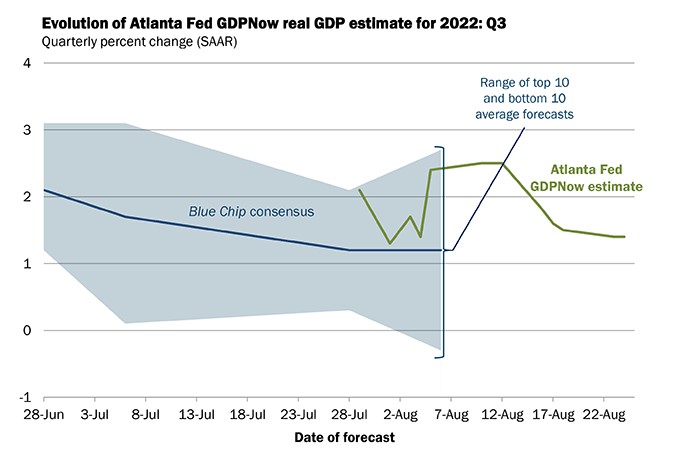

First, even before the Russian invasion, the U.S. was on the edge of a recession. The graph below shows the Atlanta Fed’s forecast for first-quarter economic growth, as of April 19. It registers an anemic 1.3% growth rate, after predicting negative growth in February.

Second, U.S. inflation climbed to its highest level in over 40 years in March. The Consumer Price Index hit 8.5% year-over-year.

The last time it was at this level was in December 1981, and at that time it was declining, not rising, after Fed boss Paul Volcker set the Fed Funds rate at a punishing 20%. (It is currently at one-quarter of 1%.) While he’s often lauded for this, the move pushed the U.S. into the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression and inflated the dollar to the point where U.S. exports became uncompetitive, spurring the manufacturing outsourcing trend that led to the country’s deindustrialization.

Today’s Fed boss, Jerome Powell, is a far meeker character. Economists expect the Fed to raise the benchmark rate by 1% over the course of four quarter-point hikes this year. This will be largely irrelevant, since the Fed is still buying billions of dollars’ worth of government and mortgage-backed bonds each month, and when it stops sometime this spring, it will be still sitting on about $8.5 trillion of those securities. The Fed’s purchase of Treasuries and MBS, which doubled the size of its balance sheet in the past two years alone, and $5 trillion in Federal deficit stimulus spending for Covid, are the proximate causes of inflation’s roaring return. (Meanwhile, total U.S. borrowing just topped $30 trillion for the first time.)

Worse, in a blunder made by the Fed during the 2008 crisis, the central bank started setting the Fed Funds rate by paying interest on bank reserve deposits. When it began scaling those reserves back in 2017, it found it could only offload about 15% before it lost control of short-term rates. These spiked and required another multi-trillion Wall Street bailout in September 2019. This means the Fed cannot sell most of the $8.5 trillion for fear of setting off another crisis.

The current level of inflation is ruinous to a currency – unless all other currencies are inflating at a similar or higher rate. That phenomenon, and the greenback’s status as a safe-haven asset, are the reasons the dollar has not been in a freefall since inflation began skyrocketing a few months back. But even if net inflation – inflation adjusted for the value of every other major currency – remains low, the dollar’s value will suffer. Even at an annual rate lower than 2% since the 2008 financial crisis, the dollar has lost 40% of its value since 2000.

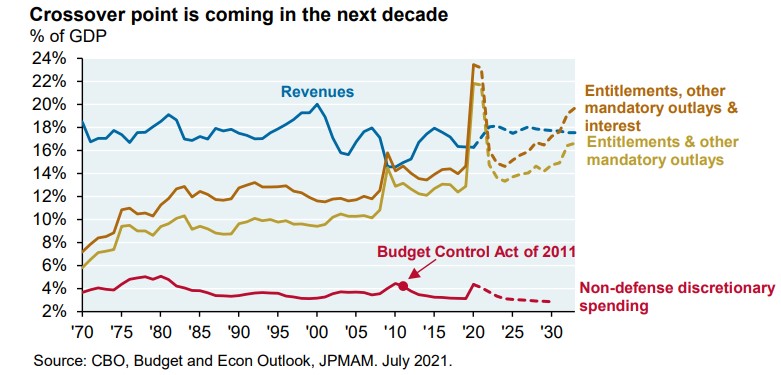

Third, government spending has become unsustainable. Michael Cembalest, market and investment strategy boss for J.P. Morgan Asset & Wealth Management, wrote in a recent note, “A fiat [normal] currency reckoning may be drawing closer: by the year 2030, U.S. Federal tax revenues will be exceeded by mandatory outlays on entitlements and interest. In other words, there will be no money left for non-defense discretionary spending which drives growth and productivity over the long run, other than through deficit spending.” He illustrated the point with the graph below.

Raising Rates as a Tool to Fight a Bigger Crisis

Those three economic headwinds – war-related economic disruptions, inflation stoked by poor policy choices, and a surfeit of government debt – interact in important ways. Inflation, for example, reduces the value of debt, hurting investors who hold government bonds and helping governments “inflate their way” out of debt. If inflation does continue to run at 7.9% per year for two years, and the interest rate on the two-year U.S. government note, currently about half a percent, stays the same, investors will lose about 7.5% of the value of their investment in each of the next two years.

A related concept is seigniorage, which, strictly speaking, is the profit a government makes by issuing a unit of currency for more than it takes to produce it. If a quarter costs a nickel to make, the government earns 20 cents. But the “right of Seigniorage” also refers to those countries that can issue all their debt in their own currency. The U.S. and Japan are the main ones, and also among the most indebted countries on earth. They theoretically cannot default because they can always just print money to cover their debt obligations. (Yes, this means that they will crater the value of their currencies, a risk that drives crypto enthusiasts’ ardor for bitcoin and its ilk – despite those “currencies” recently losing three times the amount of value in a month that the dollar is expected to lose in the coming year). However, if they inflate away their debt in this fashion, they will lose their right of Seigniorage because bondholders have long memories and will snub their debt issues.

Most countries have to issue debt in other currencies. Argentina is one. It has defaulted nine times since its independence because, when its peso falls in value, it cannot afford enough foreign currency to repay its foreign-currency loans.

Finally, the Fed has little choice but to raise rates, even if doing so almost always sparks a recession. Paradoxically, it has to raise rates because it has no tools left to fight a recession. It cannot lower rates any further, and it cannot further expand its balance sheet through more quantitative easing. It must tempt a recessionary disaster in order to have the tools to fight a potentially much bigger one.

Few Safe Ports in this Storm

Add up those issues and it makes for grim reading for the best-performing asset classes of the last few years. Corona-rally tech darlings like Tesla, Apple, Zoom, Amazon, and Netflix have been falling since November, pulling down the tech-heavy Nasdaq and the S&P 500. Investors are scaling back exposure to junk bonds and loans, finally realizing that a recession and higher rates would destroy zombie companies’ remaining cash flows and their access to the refinancings they need to survive.

So, it’s looking like Mark Twain had a point. Real estate might be the best port in the current storm for investors. But they have to be wary. Here’s some of their options, and the risks to avoid.

Direct: Residential

This has been the red-hot real estate sector in the Covid era. Massive stimulus flooded the economy with unnecessary liquidity, the Fed suppressed interest rates (and therefore mortgage rates) and Covid spurred millions of people to flee urban areas for the surrounding suburbs. The most recent S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index reported an 18.8% annual gain in December. S&P said that, “For the past several months, home prices have been rising at a very high, but decelerating rate.”

Housing bulls say residential real estate will continue to outperform because inventories of existing homes are historically low and that it will take a decade to build enough new homes to meet demand. In part this is because of reticence to invest in residential real estate after the 2008 housing bust. Barron’s wrote in February that “Construction starts on new single-family housing, … will finally top one million this year after averaging fewer than 750,000 in the previous 10 years. That would still be below the 1.6 million annual starts from 2004 to 2006, the peak years of the housing bubble.” The paper quotes a housing booster saying, “The industry would need to sustain a two-million-starts pace for a decade to bring the industry out of its current underbuilt situation.”

There are two flies in the ointment here. First, there’s a good chance the Barron’s assumption is baloney. According to Wolf Richter, “Amid shortages of materials, supplies, and labor that caused construction projects to get bogged down, and struggling with a historic spike in costs, homebuilders have amassed 406,000 single-family houses for sale (seasonally adjusted) at all stages of construction, according to date from the Census Bureau today [February 24]. This is the biggest unsold inventory since August 2008, up by 69% from a year ago, representing 6.1 months of supply.”

And remember what a good investment houses were in August 2008….

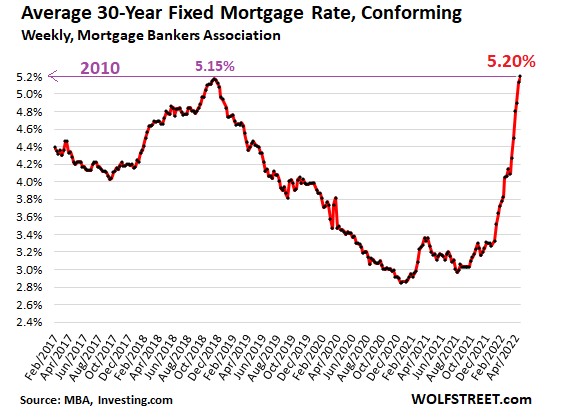

Interest rates are the second fly. Mortgages just ticked above 4%, not far from the 4.8% tipping point that cratered the housing market in 2017 and forced Fed boss Powell to stop tightening rates. Higher mortgage rates mean fewer mortgages. The burgeoning housing market fueled $3.99 trillion in mortgage originations in 2021, and a record high of $4.11 trillion in 2020. The Mortgage Bankers Association expects that to fall to $2.6 trillion in 2022.

Direct: Commercial

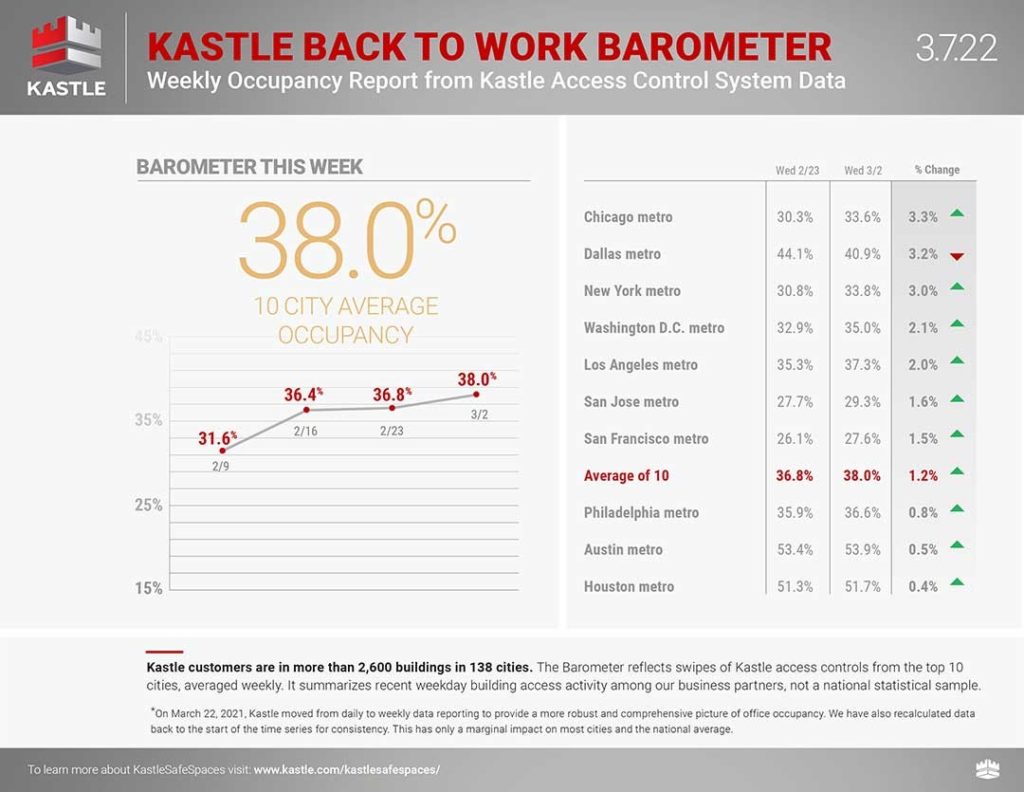

Commercial real estate is, in contrast to residential, a disaster. Work-from-home, Doordash and Amazon have seen to this. Anyone walking down a sidewalk in a major metropolitan area can’t avoid it – vast numbers of retail, restaurant and hotel properties are empty, even in pricy districts. Office occupancy rates are no better. They have been inching up but now still only average 38%, according to the Kastle Back to Work Barometer. This means companies need to shed their unused space.

Indirect: REITs

By contrast, REITs had a blowout year in 2021. The FTSE Nareit All REITs index rose 34%, beating the S&P 500’s 26% gain for the S&P 500 index. It was the strongest performance since 1976. This performance drove $140 billion in REIT M&A activity, another record, according to the Wall Street Journal.

However, REIT action was driven not by office or retail, but by self-storage and manufacturing. These are the sectors to focus on until the long-awaited back-to-work trend either materializes or sputters.

Indirect: CMBS, MBS and Synthetics

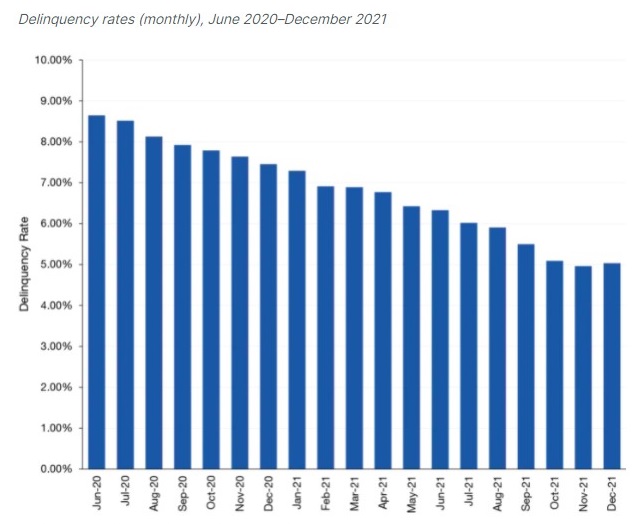

Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities did reasonably well in 2021, aided by the easing of Covid restrictions, ongoing Fed purchases, and low delinquencies. The Trepp CMBS delinquency rate for CMBS conduits fell for 19 consecutive months into December 2021, since peaking in June 2020 at around 8.6%.

MBS, by contrast, is looking like a minefield. First, when the Fed does stop buying MBS, it will remove an important backstop to the market. Second, rising rates tend to hurt MBS investors more than those in other types of bonds. That’s due to a characteristic of MBS called “negative convexity,” which is tied to the fact that these bonds have prepayment risk.

Synthetics like synthetic MBS, should be avoided entirely. They are the wrong end of some savvy hedge fund’s short bet, abetted by broker/dealers who care more about keeping the hedge fund happy than the prospects of individual investors who are lining up to be fleeced.

Indirect: Tech

Some hoped that a new breed of tech-abetted real estate flippers would transform the residential market. Instead, they went down the drain. Firms like Zillow, Redfin, Compass and Opendoor all hoped to automate real estate flipping by using algos to purchase houses, fix them up, and resell them. Their algos overpaid and most of them ended up with massive portfolios of unsold houses, leading to massive losses and plunging stocks.

Not for Novices

The cautionary tale of the tech real estate flippers shows that this asset class is not for novices. Pricing real estate assets correctly, identifying undervalued opportunities to buy, and knowing when to get out of a position all take skill. But with that skill or with a skilled advisor, real estate investments look like the best way to ride out the emerging economic storm.