The long-feared day of reckoning for the junk bond market appears to be at hand. The Federal Reserve’s 14-year suppression of interest rates on creditworthy investments has driven normally sensible investors to seek yield – any yield – in the junk market, no matter the risk, swelling it to a record $472 billion in issuance last year, according to SIFMA.

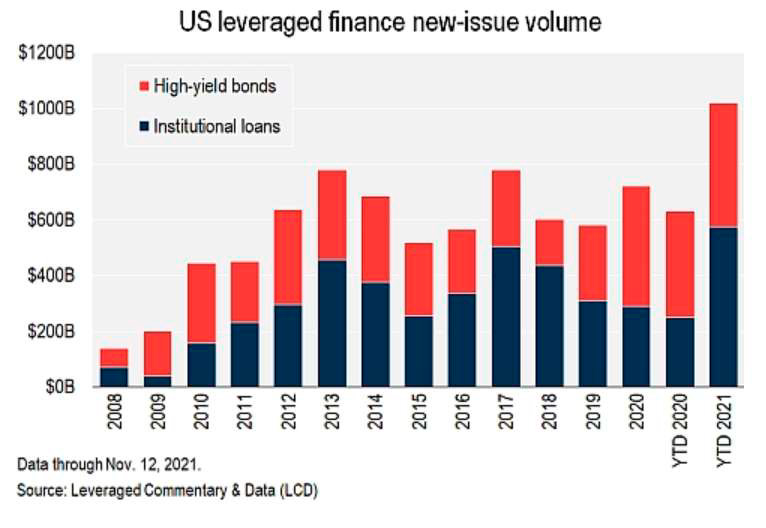

The meme-ish Wall Street acronym TINA – There Is No Alternative – normally used to justify buying overpriced stocks applies equally to fixed income investors who have found no alternative but to hold their noses and buy junk. When you add the junk loans that companies and acquisition firms like private equity shops use, the junk total for 2021 swells to over $1 trillion, according to S&P Global. The firm said this milestone was reached as “speculative-rated companies have amassed cheap funding from yield-hungry investors.”

The Fed is now reversing course. That will cause some big problems for junk issuers and investors.

The Fed’s policies to date unlinked the market from the idea that investors are supposed to be concerned with, and compensated for, taking credit risk. The yield on the Bloomberg US High Yield index stood at 4.12 percent at the end of 2021, after plumbing the mid-three percent range earlier in the year. These are rates that IBM or GE would have slavered for in their heydays. It was not that long ago that supposedly “cash-good” U.S. Treasuries paid significantly more.

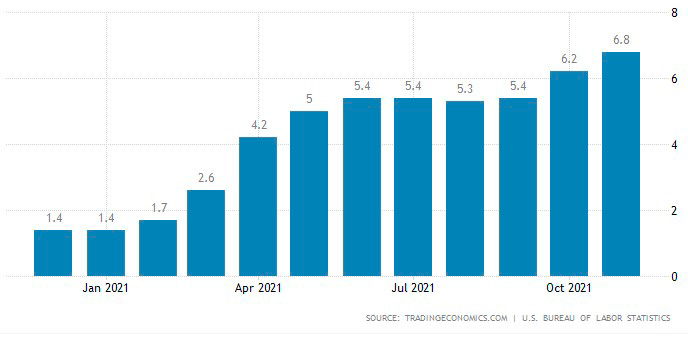

Worse, now that inflation has blasted off and hit a 31-year high, flirting with the 7 percent range, real junk yields are now firmly in negative territory. That’s to say, an investor with a junk bond paying 4 percent is actually losing 3 percent of value each year due to inflation. Because that investor is not being properly compensated for the junk bond’s credit risk – the risk the issuer will default – he is not only sure to lose money on an inflation-adjusted basis, he risks losing even more in the event of default.

The Fed’s role in this is important because it caused the problem and it is now exacerbating it. By keeping short-term rates near 0 percent since the Great Financial Crisis, the Fed has allowed borrowers to take out short-term loans at historically low rates.

By gobbling billions in Treasuries and mortgage securities each month as part of its Quantitative Easing (QE) program, it has kept the long end of the yield curve low. Yield-seeking investors who, in saner times, could have bought BBB rated investment grade paper and met their goals have been forced by the Fed’s interest-rate suppression to plunge into the single-B or worse junk world to get any yield at all.

The Fed is now exacerbating the problem because it needs to respond to inflation by raising rates and winding down its $7 trillion-plus balance sheet by ending QE in favor of Quantitative Tightening (QT).

The sign that the good times for junk borrowers – and bad times for investors – are almost over came in the January 6 release of the minutes from the previous month’s FOMC meeting, which made clear that the Fed was planning to move a lot more aggressively in raising rates and in winding down QE than the market expected. The minutes said the Fed could raise the federal funds rate “relatively soon” and implement QT “relatively soon after beginning to raise the federal funds rate.” This, the FOMC members said, would be “sooner or at a faster pace than participants had earlier anticipated.”

The release of the minutes caused the market to increase its expectation of a hike in March to more than 75 percent from 66 percent. In response, a lot of risky assets sold off, and safer ones like U.S. Treasuries advanced.

Junk-Zombie Apocalypse

The Fed’s volte-face will cause short and long-term rates to rise, and this is a real problem for junk investors and borrowers for two reasons.

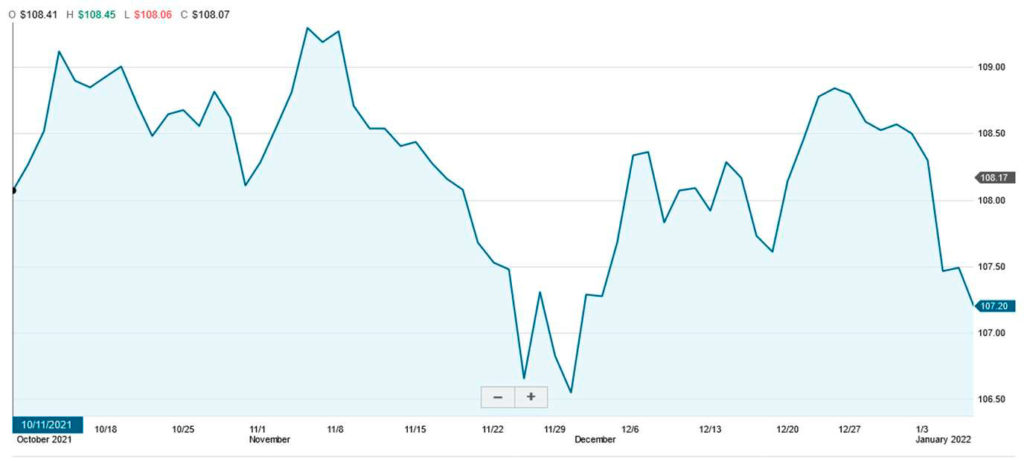

First, rising yields on creditworthy investments will drain demand from the junk market, as sensible investors find that they are able to meet their goals by purchasing investment-grade debt once again. As demand for junk bonds falls, as it did sharply in November as worries about the Omicron variant and speculation about the Fed’s plans to raise rates intensified, yields on junk will rise to more normal levels. Their prices, which move inversely to their yields, will fall, as they did in November. This can be seen in the behavior of the JNK exchange-traded fund, which tracks a portfolio of junk bonds:

Source: Schwab

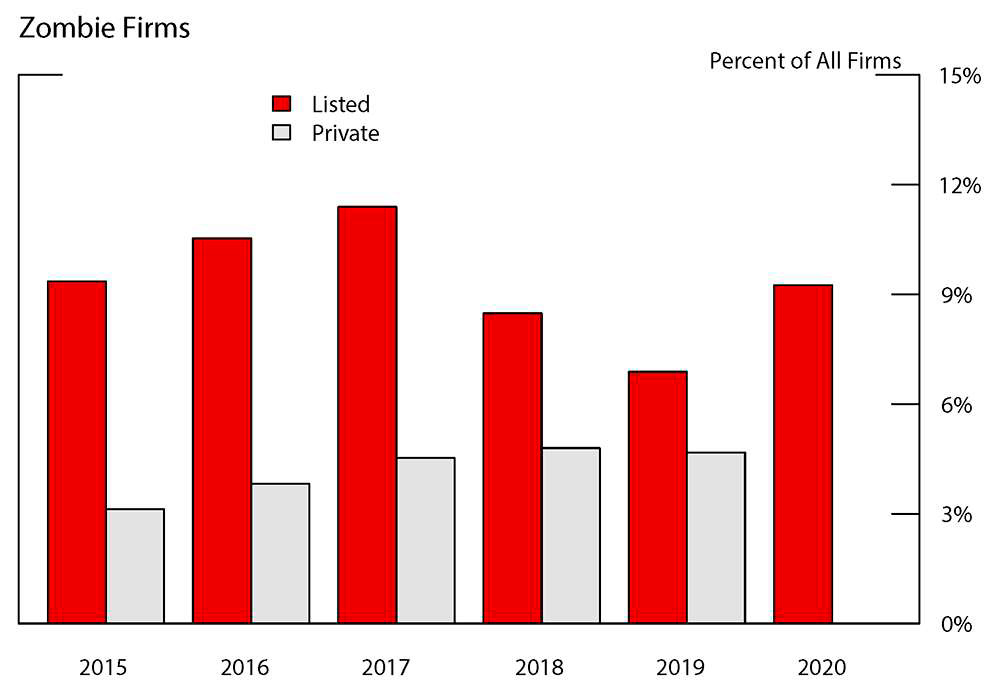

Second, investors’ complete indifference to credit quality since the beginning of the pandemic has allowed all sorts of dodgy companies to tap the junk market with remarkable success. Some of the first to wade in were in industries that would have otherwise been shunned because of the pandemic’s effect on their businesses, like cruise ship operators and regional airlines. Many of these companies are so-called zombies, which cannot fund their operations out of cash flow, and must borrow just to keep the lights on. These firms stay alive during junk market booms like the 2020-21 period, but when rates go up or investors become more discriminating, they get locked out of the market and die off.

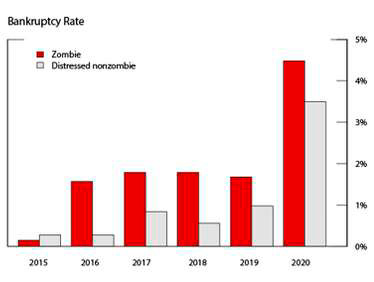

The Fed estimated in 2020 that there were only a modest number of zombie firms in the U.S., although they do go bankrupt at a far greater rate than non-zombies. However, a glance at any junk issuance calendar shows companies that are clearly on the wrong side of history lining up at the trough. Royal Caribbean Cruises raised $1 billion in early January, and was able to trim the yield on the bonds due to high demand. A cruise line with a single B+ rating, deep in junk territory and in danger of a downgrade from S&P, coasted to market with Omicron raging. Golden Nugget, a casino business whose B3 Moody’s rating puts it deep in junk territory, is looking to raise $5.6 billion of debt.

Giving it Away

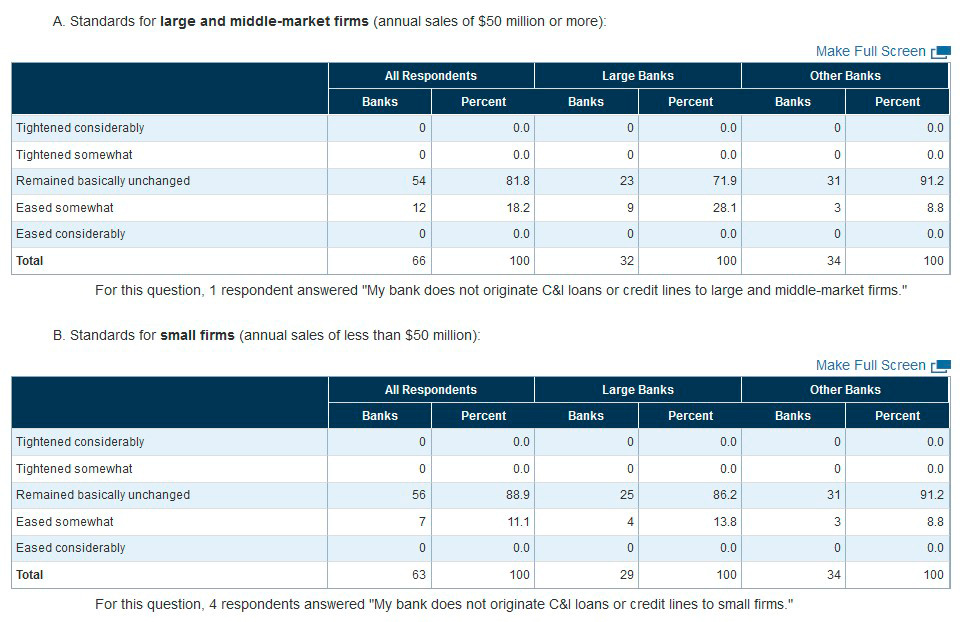

Almost as worrying as the artificial Fed-driven demand for junk is the fact that banks have been loosening their loan standards. In its most recent quarterly Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices, the Federal Reserve stated that, “Regarding loans to businesses, respondents to the October survey, on balance, reported easier standards and stronger demand for commercial and industrial (C&I) loans to large and middle-market firms over the third quarter. Banks also reported easier standards for C&I loans to small firms, while demand from small firms remained basically unchanged. For commercial real estate (CRE), banks reported easier standards for all loan categories.”

“Loosening standards” is a euphemism for “removing covenants” – the strictures in a loan agreement that a borrower must meet. These include how much additional debt it can incur, whether it may make additional strategic acquisitions, and so on. Covenants are meant to protect the bank from borrowers’ potentially promiscuous financial behavior.

Note in this excerpt from the Fed survey that, although 28 percent of banks eased standards for large borrowers, and 13 percent for small borrowers, no banks tightened standards.

Defaults Up – Recoveries Down

At the beginning of the pandemic, analysts expected a big wave of defaults by junk borrowers. In March 2020, S&P Global Ratings said the default rate for junk bonds would be 10 percent over the following 12 months, more than triple the rate of 3.1 percent in 2019. “The current recession in the U.S. this year is coming at a time when the speculative-grade market is historically vulnerable to a liquidity freeze or an earnings drop,” Nick Kraemer, head of S&P Global Ratings Performance Analytics, wrote at the time.

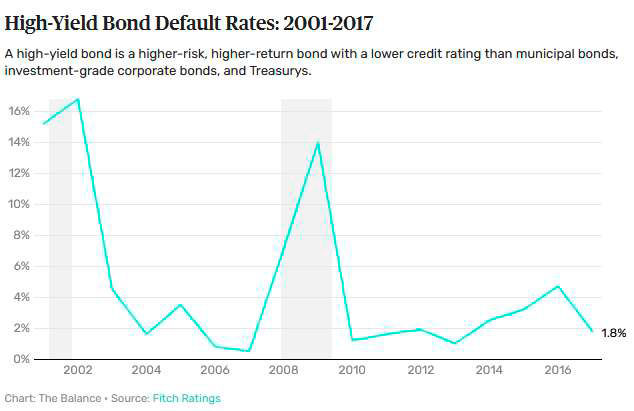

That scenario did not take place. Ratings agency Fitch reported in November that junk defaults had hit historic lows. But this passage from its report was cold comfort for anyone with a sense of history: “Fitch Ratings notes in its latest report that the 0.4% YTD U.S. high-yield bond default rate is slightly below the record low seen back in 2007.”

First, defaults are necessary and often healthy for an economy – they weed out zombies. Fitch’s data point could be seen as indicating that zombie companies are multiplying like rabbits.

More importantly, Fitch was saying that the default rate on junk bonds was just below where it was immediately before the start of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Compare it with this chart of junk default rates over time, especially where it stood at the beginning of 2007 (the gray area denotes a recession):

Another concern for junk investors is that recovery rates – what you get back via bankruptcy when a firm defaults – have been falling for years. Junk bond default rates have historically averaged 46 cents on the dollar, according to research by Edward Altman of NYU. But in 2015, it fell to 34 cents, and the following year, to 13.9 cents on the dollar. It is unclear why this is the case, but investors who get caught in the junk market’s coming transformation should prepare to lose a lot more money via defaults than they or their portfolio managers might anticipate.

What to Do

At this point, the Fed is committed to cutting the yield curve free. Investment-grade bonds will eventually become more attractive, although it is unclear if their rising yields will outpace inflation or, like junk bonds today, they will have negative yields on an inflation-adjusted basis. But given the risks involved in staying in the junk market – especially given potentially skyrocketing default rates like those seen in the Great Financial Crisis, coupled with plunging recovery rates, it seems prudent to reduce exposure to the junk market – and fast.